Lithium

In May 2016, a lithium prospect just north of the San Emidio Desert changed hands.[1]

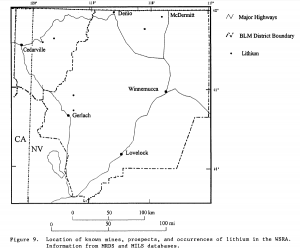

In 2003, the BLM wrote: "Lithium: Based on the anomalous occurrences of lithium noted in the east arm of the Black Rock Desert and north of Gerlach on the playa (Nash 1996) it is believed that the South Playa Area has medium potential. Volcanic rocks and related sediments near calderas ring fractures and moat sediments are also of medium potential other volcanic rocks are considered low potential. These types of rocks occur in the Lahontan cutthroat trout Area"[2]

Nash 1996 does not say anything about anomalous occurrences. Nash 1996 states:

"Geologic setting: Lithium-rich clay minerals (hectorite) form by diagenesis or hydrothermal alteration of volcanic glass. Optimum conditions are created where alteration is within a closed basin formed by block faults or caldera ring faults. At McDermitt caldera, highest concentrations of lithium are in caldera moat-filling volcaniclastic sedimentary rocks. Lithium is postulated to be leached during alteration and concentrated in the basin, eventually becoming incorporated in hectorite. Age is Tertiary to Recent."

"Another setting for lithium deposits is possible in the WSRA: Li-rich playa brines. These are known from playas elsewhere in Nevada (as near Silver Peak) and are a major by-product source of lithium at Searles Lake, CA."

"We have insufficient information to evaluate this potential environment that possibly would pertain to playas in the western and southwestern parts of the study area (Black Rock Desert, Humboldt, and Carson sinks)"

"Economic factors: The volcanic-dominated basins possibly would produce by-products such as Hg, U, zeolites, and clays. However, such by-products can contaminate Li-rich clays and limit their applications. Despite Li concentrations as high as 0.68 percent, technology for large-scale extraction of Li from hectorite has not been developed. A large production facility would need to be close to good transportation facilities for either Li-clay or a Li-salt produced at site."

"Assessment: The permissive tract is Tertiary volcanic rocks, as for diatomite and clay deposits. The more favorable areas would have normal or ring faults to create grabens or caldera moats and to focus alteration and solutions; intrusive plugs along those 12 bounding faults drive fluid flow. The McDermitt caldera is the best structural setting for these deposits; other postulated calderas in the WSRA do not have well developed moats. References: Asher-Bolinder, 1991; Rytuba and Glanzman, 1979"[3]

However Unnamed Ore Body (MRDS) cites Miller 1993[4] and U.S. Bureau of Mines, ML 7-93.[5]

Miller 1993 states: "Lithium. Three samples taken by Bohannon and Meier (1976, p. 6)[6] from the Black Rock Desert contained a maximum of 120 ppm and an average of 94 ppm lithium. Lithium content of 30 samples taken by Olson (1985, p. 9, 16) in the Black Rock Desert WSA was from 20 to 60 ppm. Selected samples analyzed for lithium during the 1992 study were consistent with these earlier analyses. Maximum lithium in a hot-spring environment was 62 ppm (sample ETMM035) taken from alluvium at the LuckyKelso prospect @I. 1, no. 31), at Soldier Meadow."

Bohannon states "The purpose of the sampling program was to determine if areas of anomalous lithium could be recognized by reconnaissance surface sampling. The resu lts, however, have been indeterminate because most large lithium deposits occur at depth and appear to be formed when deeply buried. Many may not manifest themselves at the surface at all . Nonetheless, the data derived during the surface sampling program will be presented in this report."

Bohannon states that there were three samples taken, the high was 120ppm the low was 7 ppm and the average was 94ppm. At Smoke Creek, the high was 74 ppm, the low was 43 ppm, the average was 62 ppm and there were 4 samples taken. At Winnemucca Lake, the high was 100 ppm, the low was 81 ppm, the average was 89 ppm and there were 4 samples taken.[6]

References

- ↑ Umbral Energy, "Gerlach Nevada Lithium Brine Prospect," Website, retrieved 02-Jun-2016 ([1]).

- ↑ BLM, "Black Rock Desert-High Rock Canyon Emigrant Trails National Conservation Area and Associated Wilderness, and Other Contiguous Lands in Nevada, Resource Management Plan: Environmental Impact Statement, Volume 1," 2003.

- ↑ J. T. Nash, "Resource Assessment of the US Bureau of Land Management's Winnemucca District and Surprise Resource Area Northwest Nevada and Northeast California Resource of Industrial Rock and Minerals," USGS Open File Rept 95 271, 1996.

- ↑ Miller, "Minerals in the Emigrant Trail Study Area," 1993

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of Mines Open-File Report, ML 7-93, p. 84.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bohannon, R.G., and Meier, A.L., 1976, Lithium in sediments and rocks in Nevada," U.S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 76-567, 17 p.

- Asher-Bolinder, Sigrid, 1991, Descriptive model of lithium in smectites of closed basins, in Oriss, G.J., and Bliss, J.D., eds., Some industrial mineral deposit models: descriptive deposit models,: U. S. Geological Survey Open-File Report 91-11A, p. 9-10.

- Rytuba, J.J., and Glanzman, R.G., 1979, Relation of mercury, uranium, and lithium deposits to the McDermitt caldera complex, Nevada-Oregon, in Ridge, J.D., ed., Papers on mineral deposits of western North America: Nevada Bureau of Mines and Geology, Report 33, p. 109-117.